The Divisional Court decision of Aviva v. Suarez is a recent SABS decision that has important ramifications for the public pertaining to the access to injury victims of benefits provided for in the Statutory Accident Benefits Schedule (“SABS”).

Due to the importance of the issues, a number of interested parties were granted intervenor status: the Licence Appeal Tribunal, the Ontario Trial Lawyers Association (“OTLA”), and the Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities – Ontario and Health Justice Program (the “Coalition”).

Background

The Respondent, Ms. Suarez, was involved in a motor vehicle accident on May 8, 2013. She submitted an Application for Accident Benefits to Aviva pursuant to the SABS. She sought funding for various benefits, including medical and rehabilitation benefits.

Ms. Suarez had initially been denied four chiropractic treatment plans that had been submitted to the Appellant, Aviva. Aviva had denied these treatment plans on the basis that they were not reasonable or necessary. Ms. Suarez applied to the Licence Appeal Tribunal (“LAT”) to dispute these denials.

At first instance, in the decision of DS v. Aviva Insurance Canada, 2020 CanLII 30433 (ON LAT), Adjudicator Grant found that the treatment plans should have been approved and ordered that they were payable with interest in accordance with the SABS.

Aviva sought a reconsideration of this decision on the basis that the Adjudicator had erred in determining entitlement by not addressing whether the benefits had been incurred within the meaning of s. 3(7) of the SABS. Adjudicator Grant dismissed the reconsideration request in the decision of D.S. v. Aviva Insurance Company of Canada, 2020 CanLII 45478 (ON LAT), and upheld his decision at first instance to approve the treatment plans in question (including the fourth treatment plan at issue, which was omitted from his original decision due to oversight). On the issue of whether a benefit was “incurred”, Adjudicator Grant outlined that an adjudicator could make a finding that the treatment is reasonable and necessary, and order that a benefit be payable, provided that the order complied with the SABS (such that treatment and interest are payable once the treatment is incurred and overdue).

Aviva subsequently appealed these decisions to the Divisional Court on the basis that Adjudicator Grant erred in law when he ordered the payment of treatment expenses because there was no evidence that Ms. Suarez had incurred these expenses prior to the hearing, and the LAT lacked the jurisdiction to order the payment of expenses incurred after the hearing.

It was agreed by all parties that the standard of review for a question of law was correctness.

Positions of the Parties

The Appellant, Aviva:

Aviva argued that without finding that an expense ought to be “deemed incurred” pursuant to s. 3(8) of the SABS, the LAT only had jurisdiction to order the payment of expenses that were “incurred” by Ms. Suarez, as defined in s. 3(7)(e) of the SABS, in advance of the LAT hearing. Aviva argued that the Adjudicator was obligated to consider both whether the treatment plans were improperly denied pursuant to s. 38(8) of the SABS and whether the expenses were incurred. In the absence of evidence on the issue of incurred, Aviva argued that the adjudicator ought to have dismissed the claims. Further, Aviva argued that satisfying the “incurred” definition was an essential element of a claim for medical and rehabilitation benefits under the SABS, and therefore, it was required to be established before reasonable and necessary medical rehabilitation benefits could be found payable.

Aviva also made arguments pertaining to benefits “incurred” after the LAT hearing. It argued that when it came to the payment of expenses that were incurred after the LAT hearing, the adjudicator was functus officio such that he had no jurisdiction to order payment upon the happening of a future event.

Regarding future expenses, Aviva argued in the alternative that if Ms. Suarez was allowed to incur treatment expenses following the LAT hearing, then Aviva should also be permitted to take action after the initial LAT hearing to address denials of treatment plans which complied with s. 38(3) of the SABS to avoid the mandatory consequences of s. 38(11).

The Respondent, Ms. Suarez:

Ms. Suarez, by contrast, argued that the LAT had broad statutory authority to resolve disputes between claimants and their insurers. She further argued that a decision by the LAT that an insured is entitled to coverage for treatment replaces the insurer’s denial with an approval, and as such, an order that the insurer pay for the proposed treatment plan in accordance with the SABS is the only effective remedy.

Ms. Suarez further argued that the initial Order did not offend the doctrine of functus officio as entitlement and quantum are distinct issues.

Finally, Ms. Suarez argued that an order for entitlement is final and binding, and as such, Aviva’s alternative argument that it should be permitted to cure its deficient notice following a hearing would frustrate the LAT’s system of dispute resolution.

The Intervenors:

The License Appeal Tribunal took no formal position on appeal.

OTLA submitted that the initial Order and Reconsideration decision were correct, made in the normal course and were not prospective in nature. It took the position that Aviva was seeking to overturn prior jurisprudence and that its proposed interpretation of the SABS offended its purpose as consumer protection legislation, and that the relief sought by the Appellant would render the LAT inaccessible to most claimants.

The Coalition argued that the SABS does not expressly stipulate when treatment expenses must be incurred, and that principles of statutory interpretation dictate that the provisions at issue should be interpreted in a manner that promotes access to justice. As there is an inherent power imbalance between claimants and insurers, requiring that treatment expenses be incurred prior to accessing the LAT would have an adverse impact on vulnerable populations, such as low-income individuals with disabilities.

Analysis

When examining the purpose, intent and function of accident benefits legislation, the Court ultimately reiterated the comments made by Justice MacKinnon in Arts v. State Farm Insurance Company, 2008 CanLII 25055 (ON SC) that the SABS is remedial and constitutes consumer protection legislation, and should be read with the goal of protecting motor vehicle accident victims in mind. It further noted that the purpose of assigning accident benefits disputes to the LAT was to create an efficient, fair and accessible mechanism for resolving disputes, as outlined in the Court of Appeal decision of Stegenga v. Economical Mutual Insurance Company, 2019 ONCA 615 (CanLII).

The Court agreed with Ms. Suarez’s position that LAT Orders approving treatment plans and permitting claimants to incur and submit these expenses are the only effective remedy to a denied treatment plan. Had the Appellant’s position been accepted, then claimants would have been required to fund denied treatment prior to applying to the LAT, thereby limiting claimants to pursuing only payment for treatment that they can afford to fund on their own. Vulnerable claimants with limited or no access to funds would be unable to access the LAT’s dispute resolution process for these issues, further perpetuating the power imbalances between the claimant and insurer that the legislation sought to fix.

The Court went on to conclude that allowing an insurer to issue a compliant denial following a LAT hearing would render s. 38(11) of the SABS meaningless, and the results of these LAT disputes irrelevant. The Court confirmed that determinations of entitlement and quantum are mutually exclusive issues. As such, even if the LAT determines that the claimant is entitled to the medical and rehabilitation benefits in question, he or she must still incur the expenses prior to them becoming payable. This does not prevent Aviva from being able to raise disputes regarding submitted invoices for incurred expenses, including payment of treatments that exceed the claimant’s policy limits.

Conclusions

Ultimately, the Divisional Court dismissed the appeal. The payment of the four treatment plans in question are due when incurred as defined in the SABS, and interest is payable once the treatment plans have been incurred and payment is overdue in accordance with the SABS.

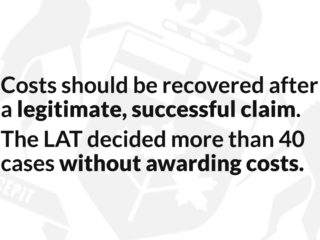

The parties had agreed on costs fixed in the amount of $5,000 inclusive of HST, payable to Ms. Suarez.

As indicated above, this is an important decision for accident benefits claimants as it provides useful commentary on the purpose, intent and function of accident benefits legislation. It reiterates that the legislation is in fact consumer protection legislation, such that it is meant to help vulnerable accident victims access the benefits that they are entitled to, and thereby increase access to justice. It further confirms that claimants are not required to fund their treatment expenses as a precursor to being able to apply to the LAT to dispute the denial of treatment plans.